Today, we are going to explore the topic of barrel finishing Scotch.

For those who may know a lot about this subject, the following will, hopefully serve as a quick and useful review. For those to whom the topic is new, I hope the discussion serves to broaden your understanding and enjoyment of Whisky.

So, let’s start at the beginning: What is Whisky?

From Webster’s… “Whisky or whiskey is a type of distilled alcoholic beverage made from fermented grain mash. Various grains (which may be malted) are used for different varieties, including barley, corn, rye, and wheat. Whisky is typically aged in wooden casks, generally made of charred white oak.”

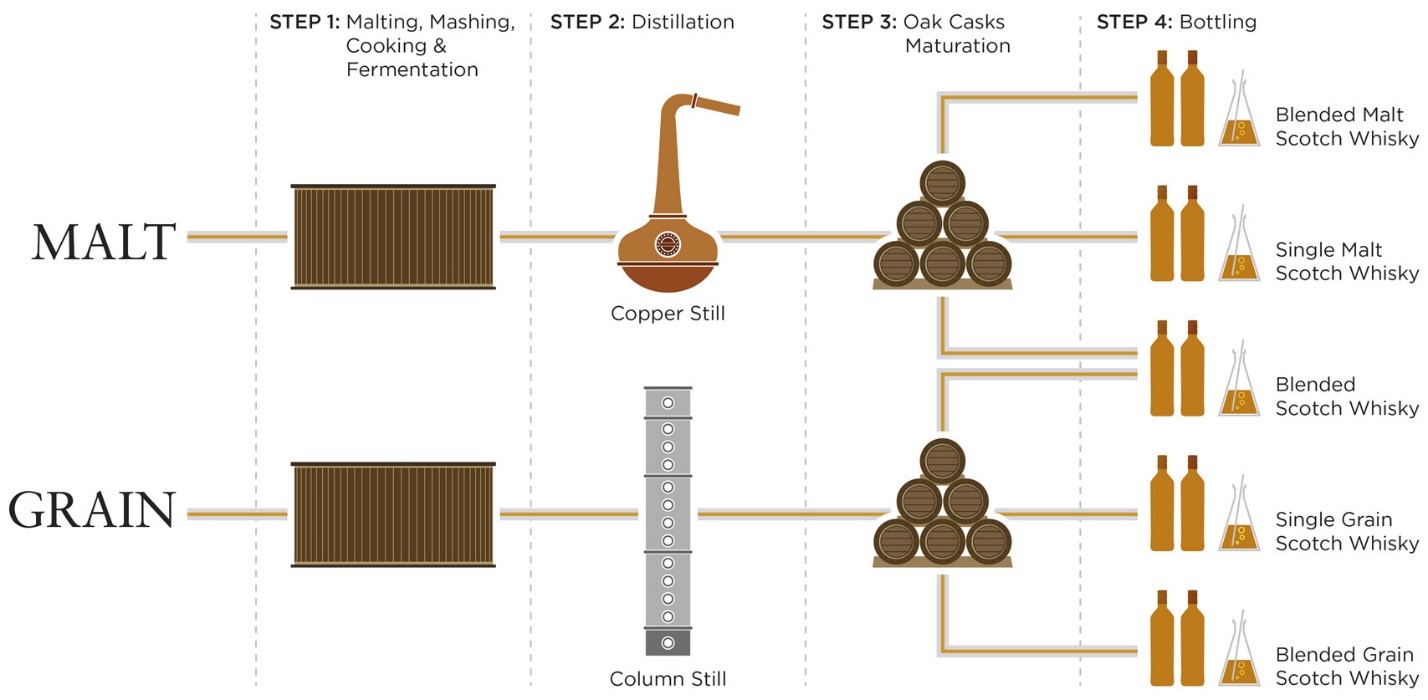

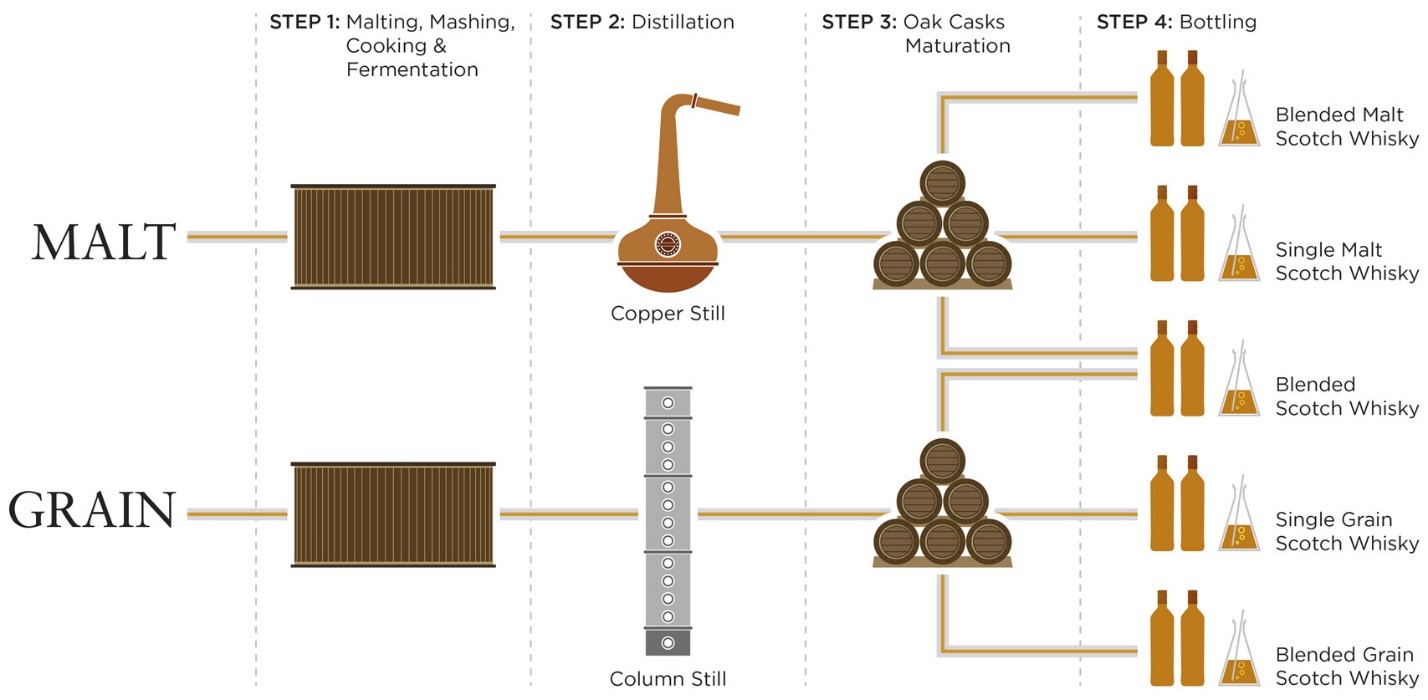

To fully understand how barrel finishing comes into play, it becomes necessary to review the process for making Scotch Malt Whisky:

- Barley is steeped in water and spread on the malting floor to germinate. This accomplishes two things – one, the water, drawn from local sources, introduces flavors into the grain (brine, iodine, peat, etc.); and two, the malting process converts the grain to fermentable sugar.

- The Barley is then dried, usually over a peat fire to both stop the germination, as well as to introduce other flavors into the grain (smoke, peat, earth, etc.).

- The dried Barley is then milled to grist, the grist is again mixed with hot water and placed in a mash tun – this mixture is called a wort.

- Yeast in now added to the wort and fermentation is undertaken, creating a beer-like liquid called a wash. This liquid is also frequently referred to as “low beer.”

- The wash is then placed in a copper, pot still called an alembic, and the liquid is distilled into the high-strength, concentrated malt spirit known as Scotch Malt Whisky. The action of distillation may involve several “runs” through the alembic until the correct degree of fineness and alcoholic strength are achieved.

- The extracted spirit is then placed in oak barrels to be aged, imparting yet more flavors and refining the spirit into a smooth, enjoyable drink.

It is at this last step that is the topic at hand.

The act of aging Whisky in oak barrels is undertaken for three main reasons:

- As a flavor additive – a properly prepared oak barrel will instill certain flavors into the spirit, such as vanilla, coconut, toasty wood and caramel sweetness.

- As a filter – a properly prepared oak barrel will act as a filter to remove undesirable compounds from the spirit that may detract from the overall character of the spirit.

- As a chemical synthesizer – A properly prepared oak barrel will physically interact with the spirit to alter its chemical make up and as a result, improve the flavor and structure of the spirit. This happens as a result of specific chemical reactions, as well as concentration of the spirit through absorption and evaporation.

There are five constituent parts of oak that contribute to the maturation of the spirit:

- Cellulose – No flavor effects but it is critical to maintaining barrel structure.

- Hemicellulose – Contain simple sugars, which when properly prepared (heated and toasted) contribute body, toasty caramel notes and color.

- Lignin – A binding agent to cellulose, which when properly prepared (heated and toasted) contribute vanilla, spice and smoke notes.

- Oak Tannin – Enable oxidation, which create delicate fragrances in the spirit through chemical changes that form esters and acetals over time.

- Oak Lactones – Resulting from the lipids in oak, which when properly prepared (during charring) pass along strong woody flavors with coconut overtones. American oak has more lactone than European oak.

Three species of oak are used in the production of oak barrels, and they impart subtly different characteristics to the spirit:

- Quercus Alba: White, American Oak. The most commonly used wood for Whisky aging. Emphasizes vanilla flavors because of high concentration of oak lactones. Larger pore structure increase absorption and evaporation rates.

- Quercus Petraea: Sesille, European Oak, primarily France. The most commonly used wood for Wine aging. Fine structure emphasizes fewer tannins and slower maturation rates.

- Quercus Robur: Pedunculate, European Oak, primarily Spain, but found throughout. The most commonly used wood for Cognac and Sherry. Broad structure and grain make-up emphasize oxidation rates which contribute more raisin and prune-like flavors.

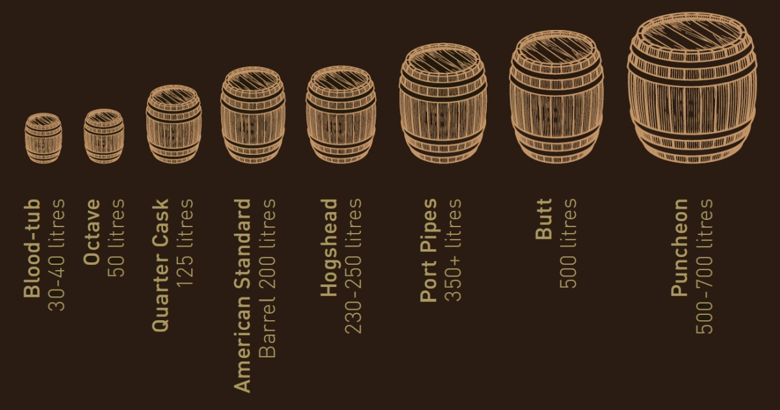

The most common oak barrels used for the initial aging of Whisky are:

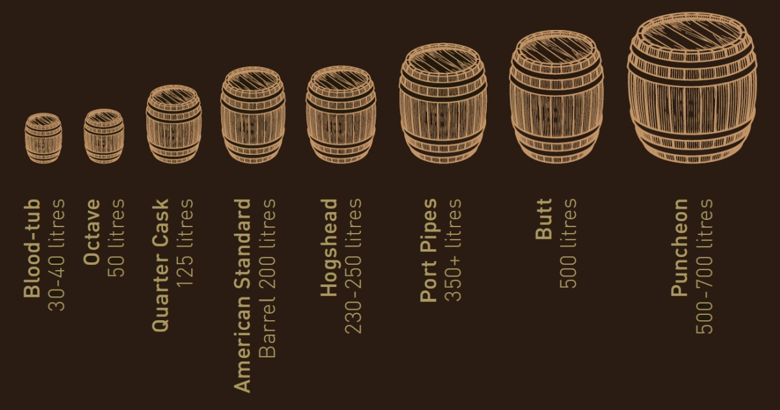

Ex-Bourbon Hogsheads – 225-250 Liters – Because these barrels are used originally in the aging of Bourbon, the barrels are charred – meaning the inside of the cask is literally set on fire for a short period of time, which creates a black charred layer. There are various levels of charring which will have different effects on the spectrum of compounds and flavors the barrel will impart to the maturing Whisky, such as enhanced vanillin, lactones, toastiness, spiciness, and tannins. Charring casks causes further transformation. Char (carbon) removes sulfur compounds and immaturity from new spirit. Ex-Bourbon Hogsheads are typically charred for 40 seconds to 1 minute, but some distilleries have experimented with charring times of up to 3-4 minutes. The result of charring also changes the chemical composition of the inside surface of the barrel, resulting in caramelized oak lignin, which creates both sweetness and red coloration that leech into the aging Whisky. When the barrel is newly charred is when this leeching has the most dramatic effect, so by the time the barrel is used for Scotch Whisky aging, the impact is lessened.

Ex-Sherry Butt/Pipe – 450-500 Liters – Sherry casks are only toasted and not charred. The casks used to mature Oloroso are the most popular for aging Scotch Whisky. Sherry casks can be made of American Oak, but this is usually for barrels used in the production of Fino Sherries and are generally not used for aging Scotch Whisky. European Oak generally adds more flavor than American Oak – ex-sherry cask matured Whisky tends to be more full-bodied than ex-Bourbon cask matured ones, which is a result of the differences in varietal characteristics of the wood, as opposed to the prior contents of the barrel.

The majority of Scotch Malt Whisky is only aged in the aforementioned barrels. This produces a homogenous end product that consumers can count on tasting the same from year to year.

However, it is common for distillers to experiment with other cask types in the “finishing” of a Scotch Whisky. Legally, Scotch must be aged for a minimum of three years before it can be bottled and sold. Most well-regarded distilleries age their Scotch for far longer. During the maturation process, the distiller may select certain casks for special finishing. If this decision is made, the spirit is transferred to a special cask for a specified period of time. The special cask is referred to as a “finishing cask,” and can be taken from a wide variety of prior usage casks.

Common cask types used to “finish” a Scotch are ex-Port, ex-Sherry, ex-Rum, and ex-Wine casks. The use of a finishing cask will subtly add other flavors to a Scotch. The flavors added are a direct result of the liquid that was previously aged in the cask. For instance, Port can be very sweet and depending on the style, can have a wide range of flavors. Placing Scotch is a cask that previously held Port, will likely impart some sweetness to the Scotch, as well as some of the other flavor elements left over in the cask. Distillers spend a lot of time and money experimenting with cask types to create expressions of their Scotch that are presumably subtly better, if not more intriguing than their standard bottlings.

Some call this marketing gimmickry while others call it the true essence of an artiste. As a wine and spirits connoisseur, I call it fun and educational.

To that end, I recently had the pleasure of conducting a Scotch Malt Whisky tasting that examined the use of various finishing casks and their resulting effects. The group focused on two flights of Scotch Malt Whisky from two producers.

Glen Moray – Elgin Classic Selection – Special Cask Series

Glen Moray is a Speyside distillery producing single malt Scotch Whisky, situated on the banks of the River Lossie in Elgin. Glen Moray started production in September 1897. The distillery was sold in 2008 by the Glenmorangie Company Ltd. to La Martiniquaise.

In my opinion, Glen Moray is one of the more under-valued single malts in the market today. Their product is consistently pleasing and priced very well.

We started the flight with the Glen Moray 12-year-old Single Malt Whisky. The malt is a classic Speyside, with an easy drinking style and creamy, vanilla nose. The malt set a good baseline by which to measure the three special cask finishes.

Sherry Cask Finish This example is finished for eight months in Oloroso Sherry casks. The resulting malt has a drier nose with hints of cinnamon, toffee and dried fruits. On the palate the malt is seductive with creamy vanilla and exotic spice notes. Very well-balanced and smooth.

Cabernet Sauvignon Cask Finish This example is finished for eight months in Cabernet Sauvignon Wine casks. The resulting malt has a soft, almost fruity nose with cedar and menthol hints. Intriguing palate with hints of cherry and violet notes. Vanilla, toffee and iodine on the finish. Smooth and well-balanced.

Port Cask Finish This example is finished for eight months in Port Wine pipes from Porto Cruz, a very popular Port producer. The resulting malt is drier on the nose and palate than the Sherry Cask, with cocoa and cedar notes. Subtle on the palate with a light toffee and butterscotch finish. No perceptible smoke or peat. Very well balanced and smooth.

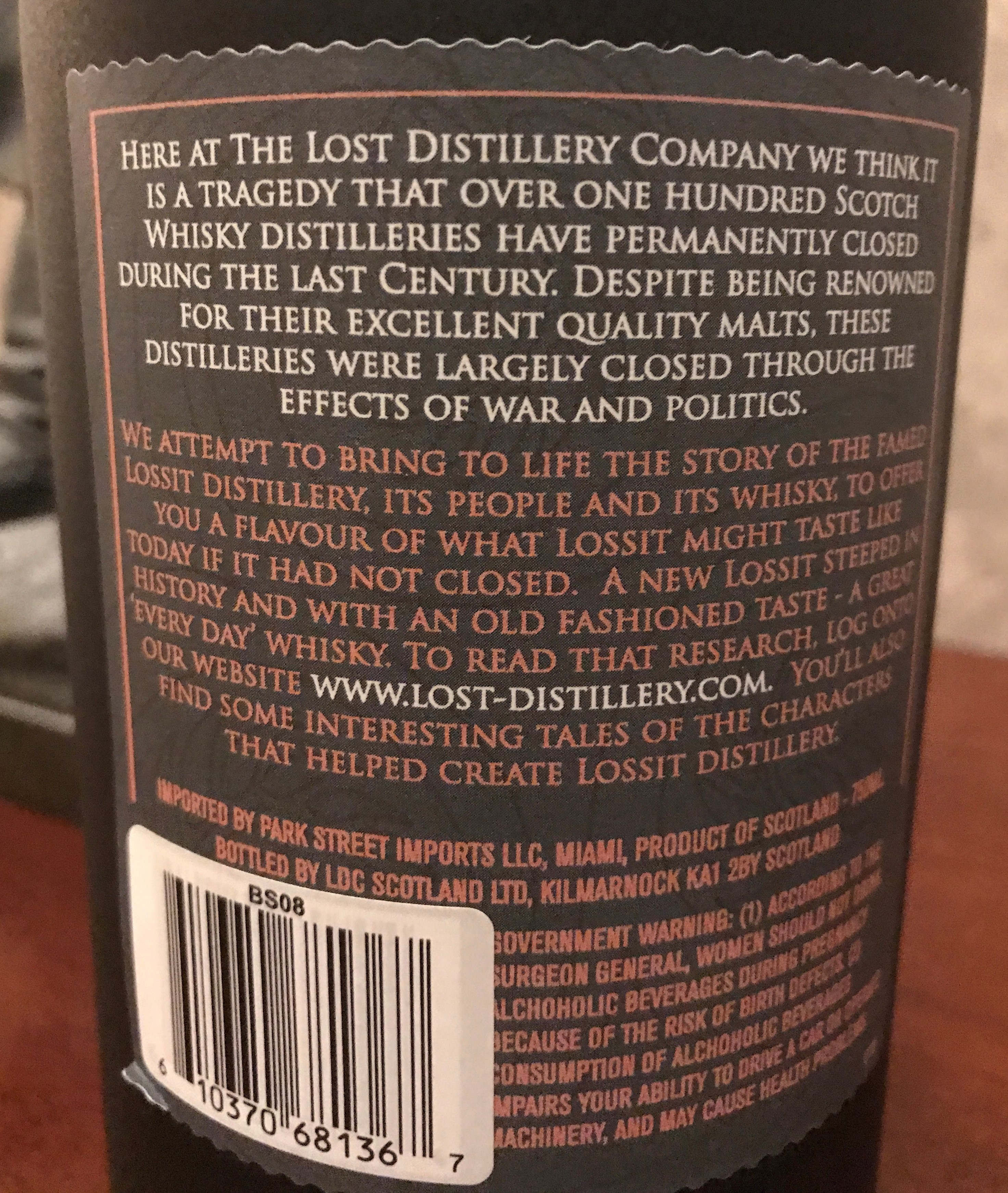

Lost Distillery Company – Lossit – Loch & Key Society Special Cask Series

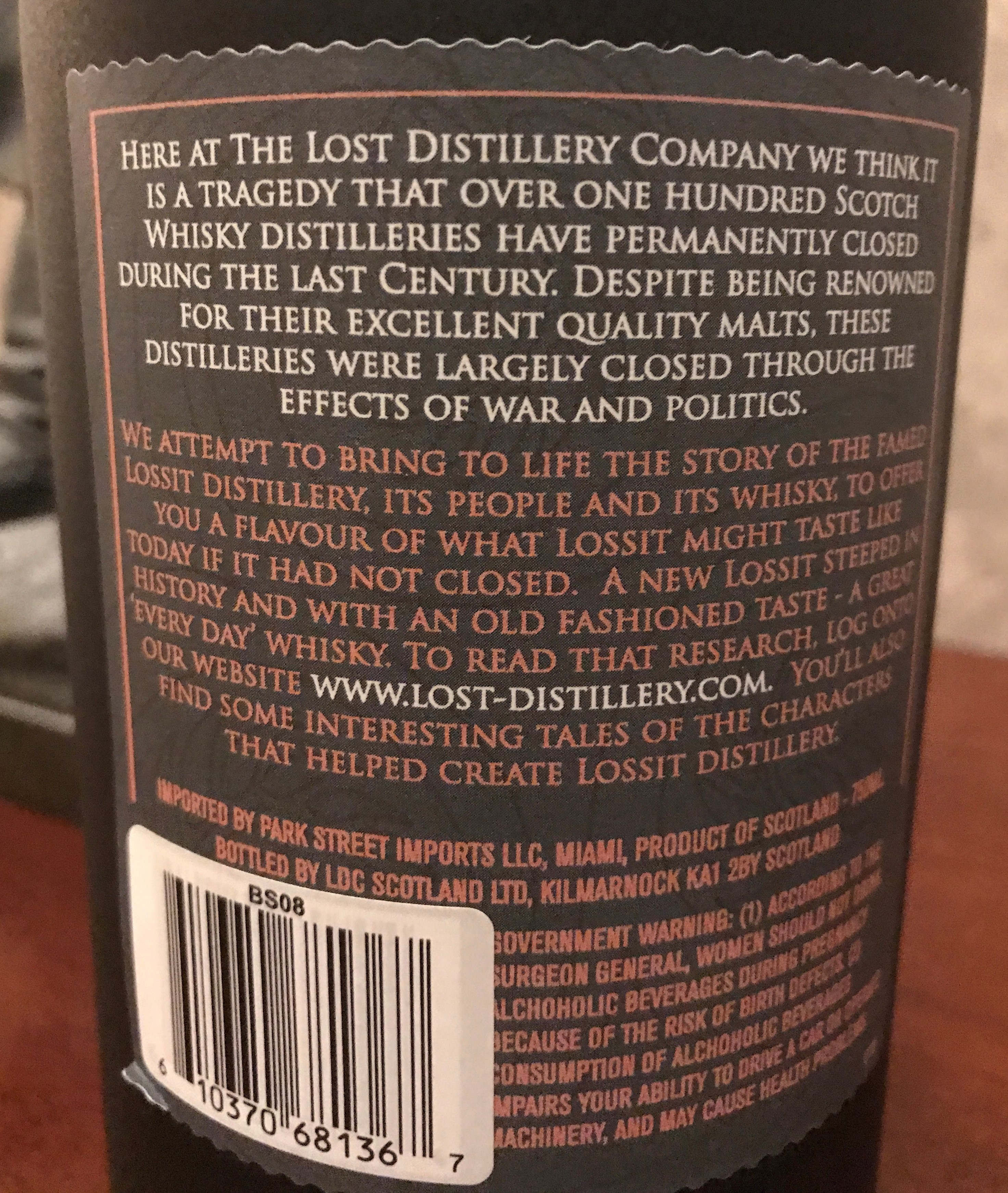

The Lost Distillery Company believes “it is a tragedy that over one hundred Scotch Whisky distilleries have been permanently closed during the last century.” The Lost Distillery Company has breathed life back into many of these distilleries, by painstakingly researching all of the important elements that made a distillery unique and then taking their research to heart by producing archival bottles of these magnificent ghosts.

One such “ghost” is Lossit, a small, farm-distillery founded in 1817 by Malcolm McNeill in the Islay distillery at Lossit Kennels, near Port Askaig. In its earliest years, Lossit was the biggest producer of whisky on Islay until they closed in 1867. Lossit used either ex-sherry, or pure oak casks. These sherry casks, infused sweet, zesty fruit flavors into the aging spirit. Fragrant peaty notes fused with floral notes from the bere barley. They sourced water from Loch Lossit.

This series of malts was produced especially for the Loch & Key Society and had a number of limited bottle expressions, all based on the standard cask finished Lossit. I did not get to taste the standard bottling, but reliable tasting notes suggest: A nose of sherry and dried fruits with strong peat, smoke and brine. Smoky and peaty on the palate with fruity sweetness and spiciness on the finish. Good mid-palate weight and a long, smooth finish. Well-balanced.

The special cask finishes that were tasted, are as follows:

Ribera Del Duero Cask Finish This example is finished in the red wine casks of Ribera Del Duero from Spain. The resulting malt is heavily peated with campfire and iodine notes. Slightly sweet with red fruit elements in the nose and light cherry fruit on the palate. Well-balanced.

Port Cask Finish This example is finished in Port Wine pipes. The resulting malt has pronounced chocolate and marzipan notes. Campfire and peat on the finish. Smooth and very well-balanced.

Pedro Ximenes Sherry Cask Finish This example is finished in PX Sherry casks. The resulting malt is wonderfully rich, crème brûlée with wisps of campfire smoke and peat on the finish. Well-balanced and smooth.

Rum Cask Finish This example is finished in Rum casks. The resulting malt is not as sweet as either the Port or PX Sherry Cask finishes, with no campfire and peat on the aftertaste. Still smooth and well-balanced. Sweet mid-palate with vanilla and allspice.

April is the time of year that is perfect for “shoulder season” cocktails, of which the Angel Face is definitely one. What makes a “shoulder season” cocktail, you ask? “Shoulder season” cocktails are moderate in “weight” and “depth.” By weight, we allude to the feel of the cocktail on one’s palate, the “heaviness,” so to speak. By depth, we allude to a cocktail’s level of unfolding complexity. If Winter cocktails are heavy, warming libations that evoke thoughtfulness in their deeply unfolding complexity, Summer season cocktails are light and refreshing, thirst-quenching and not necessarily thought-provoking.

April is the time of year that is perfect for “shoulder season” cocktails, of which the Angel Face is definitely one. What makes a “shoulder season” cocktail, you ask? “Shoulder season” cocktails are moderate in “weight” and “depth.” By weight, we allude to the feel of the cocktail on one’s palate, the “heaviness,” so to speak. By depth, we allude to a cocktail’s level of unfolding complexity. If Winter cocktails are heavy, warming libations that evoke thoughtfulness in their deeply unfolding complexity, Summer season cocktails are light and refreshing, thirst-quenching and not necessarily thought-provoking. The Periodista, or “The Journalist” cocktail harkens back to a recipe in Harry Craddock’s Savoy Cocktail Book and is originally cribbed as a Gin-based libation. Borrowing elements from the “perfect” Martini, the Craddock recipe combines sweet and dry Vermouth to create balance and mid-palate weight. A touch of Curaçao suggests an exotic, faraway island, perhaps Cuba. Refreshing and contemplative, the drink is an alluring treat.

The Periodista, or “The Journalist” cocktail harkens back to a recipe in Harry Craddock’s Savoy Cocktail Book and is originally cribbed as a Gin-based libation. Borrowing elements from the “perfect” Martini, the Craddock recipe combines sweet and dry Vermouth to create balance and mid-palate weight. A touch of Curaçao suggests an exotic, faraway island, perhaps Cuba. Refreshing and contemplative, the drink is an alluring treat.